Sums, series, and products in Diophantine approximation

Abstract

There is not much that can be said for all and for all about the sum

However, for this and similar sums, series, and products, we can establish results for almost all using the tools of continued fractions. We present in detail the appearance of these sums in the singular series for the circle method. One particular interest of the paper is the detailed proof of a striking result of Hardy and Littlewood, whose compact proof, which delicately uses analytic continuation, has not been written freshly anywhere since its original publication. This story includes various parts of late 19th century and early 20th century mathematics.

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Bernoulli polynomials, the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula, and Euler’s constant

- 3 Background

- 4 Preliminaries on continued fractions

- 5 Diophantine conditions

- 6 Sums of reciprocals

- 7 Weyl’s inequality, Vinogradov’s estimate, Farey fractions, and the circle method

- 8 Discrepancy and exponential sums

- 9 Dirichlet series

- 10 Power series

- 11 Product

- 12 Conclusions

1 Introduction

In this paper we survey a class of estimates for sums, series, and products that involve Diophantine approximation. We both sort out a timeline of the literature on these questions and give careful proofs of many lesser known results. Rather than being an open-pit mine for the history of Diophantine approximation, this paper follows one vein as deep as it goes.

For , we write , the distance from to a nearest integer. In this paper we give a comprehensive presentation of estimates for sums whose th term involves and determine the abscissa of convergence and radius of convergence respectively of Dirichlet series and power series whose th term involves . We also give a detailed proof of a result of Hardy and Littlewood that

for almost all .

We either prove or state in detail and give references for all the material on continued fractions and measure theory that we use in this paper. Many of the results we prove in this paper do not have detailed proofs written in any books, and the proofs we give for results that do have proofs in books are often written significantly more meticulously here than anywhere else; in some cases the proofs in the literature are so sketchy that the proof we give is written from scratch, for example Lemma 9. Our presentation of Hardy and Littlewood’s estimate for makes clear exactly what results in Diophantine approximation one needs for the proof.

In the next section we introduce the Bernoulli polynomials, the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula, and Euler’s constant, which we shall use in a few places. Because the calculations are similar to what we do in the rest of this paper and because we want to be comfortable using Bernoulli polynomials, we work things out from scratch rather than merely stating results as known. In the section after that we summarize various problems that involve sums of the type we are talking about in this paper.

2 The Bernoulli polynomials, the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula, and Euler’s constant

For , the Bernoulli polynomial is defined by

| (1) |

The Bernoulli numbers are , the constant terms of the Bernoulli polynomials. For any , using L’Hospital’s rule the left-hand side of (1) tends to as , and the right-hand side tends to , hence . Differentiating (1) with respect to ,

so and for we have , i.e.

Furthermore, integrating (1) with respect to on gives, since ,

hence and for ,

The first few Bernoulli polynomials are

The Bernoulli polynomials satisfy the following:

hence

| (2) |

In particular, for , . The identity (2) yields Faulhaber’s formula, for and positive integers ,

| (3) |

The following identity is the multiplication formula for the Bernoulli polynomials, found by Raabe [122, pp. 19–24, §13].

Lemma 1.

For , , and ,

Proof.

We remark that for prime and for , one uses Lemma 1 to prove that there is a unique -adic distribution on the -adic integers such that [80, p. 35, Chapter II, §4], called a Bernoulli distribution.

For , let be the greatest integer , and let , called the fractional part of . Write and define the periodic Bernoulli functions by

For , because , the function is continuous. For define its Fourier series by

For , one calculates and using integration by parts, for . Thus for , the Fourier series of is

For , , from which it follows that converges to uniformly for . Furthermore, for [102, p. 499, Theorem B.2],

Thus for example,

The Euler-Maclaurin summation formula is the following [102, p. 500, Theorem B.5]. If are real numbers, is a positive integer, and is a function on an open set that contains , then

Applying the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula with yields [102, p. 503, Eq. B.25]

Using , taking the exponential of the above equation gives Stirling’s approximation,

Write . Because is concave,

which means that the sequence is nonincreasing. For , because is positive and nonincreasing,

hence . Because the sequence is positive and nonincreasing, there exists some nonnegative limit, , called Euler’s constant. Using the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula with , as ,

which is

As , the function is integrable on ; let . Since ,

f. But as , from which it follows that and thus

3 Background

For , let be the greatest integer and let . It will be handy to review some properties of . For it is immediate that . For we have , which means , and using this is , therefore

For , , and ,

For a positive integer and for real ,

There is a unique , , such that and , and therefore and , consequently and , which means , from which finally we get and so . But

and using ,

This identity is proved by Hermite [65, pp. 310–315, §V].

The Legendre symbol is defined in the following way. Let be an odd prime, and let be an integer that is not a multiple of . If there is an integer such that then , and otherwise . In other words, for an integer that is relatively prime to , if is a square mod then , and if is not a square mod then . For example, one checks that there is no integer such that , and hence , while , and so .

If and are distinct odd primes, define integers , , by

namely, is the remainder of when divided by . We have . Let be the number of such that . It can be shown that [59, p. 74, Theorem 92]

this fact is called Gauss’s lemma. For example, for and we work out that

and hence , so ; on the other hand, , hence . With

it is known that [59, pp. 77-78, §6.13]

And it can be shown that [59, p. 76, Theorem 100]

| (4) |

Thus

This is Gauss’s third proof of the law of quadratic reciprocity in the numbering [7, p. 50, §20]. This proof was published in Gauss’s 1808 “Theorematis arithmetici demonstratio nova”, which is translated in [140, pp. 112–118]. Dirichlet [38, pp. 65–72, §§42–44] gives a presentation of the proof. Eisenstein’s streamlined version of Gauss’s third proof is presented with historical remarks in [93]. Lemmermeyer [95] gives a comprehensive history of the law of quadratic reciprocity, and in particular writes about Gauss’s third proof [95, pp. 9–10]. The formula (4) resembles the reciprocity formula for Dedekind sums [123, p. 4, Theorem 1].

Gauss obtains (4) from the following [140, p. 116, §5]: if is irrational and is a positive integer, then

| (5) |

which he proves as follows. If , then . Therefore

Bachmann [6, pp. 654–658, §4] surveys later work on sums similar to (5); see also Dickson [35, Chapter X]. If and are relatively prime, then

and so

Hence

| (6) |

There is also a simple lattice point counting argument [118, p. 113, No. 18] that gives (6).

In 1849, Dirichlet [37] shows that

where denotes the number of positive divisors of an integer . (This equality is Dirichlet’s “hyperbola method”.) He then proves that

Hardy and Wright [59, pp. 264–265, Theorem 320] give a proof of this. Finding the best possible error term in the estimate for is “Dirichlet’s divisor problem”. Dirichlet cites the end of Section V Gauss’s Disquisitiones Arithmeticae as precedent for determining average magnitudes of arithmetic functions. (In Section V, Articles 302–304, of the Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, Gauss writes about averages of class numbers of binary quadratic forms, cf. [36, Chapter VI].)

Define to be if ; if then there is an integer for which for all integers , and we define to be . Riemann [125, p. 105, §6] defines

for any , the series converges absolutely because . Riemann states that if and are relatively prime and , then

thus

and hence that is discontinuous at such points, and says that at all other points is continuous; see Laugwitz [94, §2.1.1, pp. 183-184], Neuenschwander [108], and Pringsheim [119, p. 37] about Riemann’s work on pathological functions. The role of pathological functions in the development of set theory is explained by Dauben [32, Chapter 1, p. 19] and Ferreirós [49, Chapter V, §1, p. 152].

For any interval and any , it is apparent from the above that there are only finitely many for which , and Riemann deduces from this that is Riemann integrable on ; cf. Hawkins [63, p. 18] on the history of Riemann integration. Later in the same paper [125, p. 129, §13], Riemann states that the function

is not Riemann integrable in any interval.

In 1897, Cesàro [28] asks the following question (using the pseudonym, and anagram, “Rosace” [112, p. 331]). Let . Is the series

| (7) |

convergent for all non-integer ? This is plausible because the expected value of is 0. Landau [89] answers this question in 1901. Landau proves that if there is some such that

where is a nonnegative function such and such that converges, then (7) converges. And he proves that if is rational then (7) diverges. We return to this series in §9.

Also in 1898, Franel [52] asks whether for irrational and for we have

Then in 1899, Franel [53] asks if we can do better than this: is the error term in fact ? Cesàro and Franel each contributed many problems to L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens, the periodical in which they posed their questions. Information about Franel is given in [82].

Lerch [96] answers Franel’s questions in 1904. If is irrational and is a convergent of (which we will define in §4), then using Theorem 2 (from §4) we can show that if then . Lerch uses this and (6) to show that if is irrational and is a convergent of then

Lerch states that if the continued fraction expansion of has bounded partial quotients (defined in §4) then, for any positive integer ,

Lerch only gives a brief indication of the proof of this. This result is proved by Hardy and Littlewood in 1922 [57, p. 24, Theorem B3], and also in 1922 by Ostrowski [110, p. 81]. On the other hand, Lerch also constructs examples of such that, for some positive integer ,

Nevertheless, in 1909 Sierpinski [135] proves that if is irrational then

A bibliography of Lerch’s works is given in [139]. Lerch had written earlier papers on Gauss sums, Fourier series, theta functions, and the class number; many of his papers are in Czech, but some of them are in French, several of which were published in the Paris Comptes rendus. Several of Lerch’s papers are discussed in Cresse’s survey of the class number of binary quadratic forms [36, Chapter VI].

In 1899, a writer using the pseudonym “Quemquaeris” [121] (“quem quaeris” = “whom you seek”) asks if we can characterize such that for all irrational the series

converges. In particular, the writer asks if satisfies this. In the same year, de la Vallée-Poussin [34] answers this question. (There are also responses following de la Vallée-Poussin’s by Borel and Fabry.) For a given function , de la Vallée-Poussin shows that if we have for all , for the th partial quotient of and the denominator of the th convergent of , then the series

will diverge. Hardy and Littlewood prove numerous results on similar series, e.g. for for real and for certain classes of , in their papers on Diophantine approximation [61]. In 1931, Walfisz [152, p. 570, Hilfssatz 4] shows, following work of Behnke [13, p. 289, §16], that for almost all irrational , if then

where . Walfisz’s paper includes many results on related sums.

In 1916, Watson [153] finds the following asymptotic series for :

where is Euler’s constant and are the Bernoulli numbers. Truncating the asymptotic series and rewriting gives

For example, computing directly we get , and computing the right-hand side of the above formula without the error term we obtain A cleaner derivation of the asymptotic series using the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula is given later by Williams [155].

Early surveys of Diophantine approximation are given by Bohr and Cramér [20, pp. 833–836, §39] and Koksma [81, pp. 102–110]. Hlawka and Binder [66] present the history of the initial years of the theory of uniform distribution. Narkiewicz [106, pp. 82–95, §2.5 and pp. 175–183 §3.5] gives additional historical references on Diophantine approximation. The papers of Hardy and Littlewood on Diophantine approximation are reprinted in [61]. Perron [113] and Brezinski [23] give historical references on continued fractions, and there is reliable material on the use of continued fractions by 17th century mathematicians in Whiteside [154]. Fowler [51] presents a prehistory of continued fractions in Greek mathematics.

4 Preliminaries on continued fractions

Let

Let be Lebesgue measure on , and let .

For positive integers , we define

For example, .

Let be the set of positive integers. We call a continued fraction, and we call the th partial quotient of . If there is some such that for all then we say that has bounded partial quotients. We call the th convergent of . For let

with positive integers that are relatively prime, and set

One can show by induction [44, p. 70, Lemma 3.1] that for we have

| (8) |

We have

and from (8) we get for all that

and

Since the are positive integers we get by induction that for all ,

| (9) |

In fact, setting , for , with the th Fibonacci number, as we check by induction that

Taking determinants of (8) gives us for all that

| (10) |

and then by induction we have for all ,

For any , as this sequence of sums converges and we denote its limit by . We have for all ,

Since the right hand side is an alternating series we obtain for ,

| (11) |

and

| (12) |

and

| (13) |

For , we say that , , is a best approximation to if and for . The following theorem shows in particular that the convergents of a continued fraction are best approximations to [127, p. 22, Chapter 2, §3, Theorem 1].

Theorem 2 (Best approximations).

Let . For any ,

If , then for any ,

Proof.

Write and let . Applying (10),

Let

Then

and

In particular, . Suppose by contradiction that . Then , and as it must then be that and . But , , and are together a contradiction. Therefore . Either or . For ,

which is the claim. For we use the fact and . If then is contradicted, and if then is contradicted. Therefore and have different signs, say and . Furthermore, we get from (13) that

Therefore

hence

which is the claim. ∎

The above theorem says, a fortiori, that the convergents of are best approximations to . It can also be proved that if , , is a best approximation to then is a convergent of [92, p. 9, Theorem 6]. Cassels [27, p. 2, Chapter I] works out the theory of continued fractions according to this point of view. Similarly, Milnor [101, p. 234, Appendix C] works out the theory of continued fractions in the language of rotations of the unit circle.

We define the Gauss transformation by for , and we define by

One can check that if then [44, p. 73, Lemma 3.2]. (Namely, the value of a nonterminating continued fraction is irrational.) One can prove that is injective [44, p. 75, Lemma 3.4], and for that [44, p. 78, Lemma 3.6]

Therefore is a bijection. Moreover, is a homeomorphism, when has discrete topology, has the product topology, and has the subspace topology inherited from [44, p. 86, Exercise 3.2.2]. That and are homeomorphic can also be proved without using continued fractions [2, p. 106, Theorem 3.68]. In descriptive set theory, the topological space is called the Baire space, and the Alexandrov-Urysohn theorem states that has the universal property that any nonempty Polish space that is zero-dimensional (there is a basis of clopen sets for the topology) and all of whose compact subsets have empty interior is homeomorphic to [75, p. 37, Theorem 7.7]. Some of Baire’s work on is described in [71, pp. 119–120] and [5, pp. 349, 372].

For and for , for and . For let , so if then . Then for ,

For , , and for ,

and for , . Differentiability and dynamical properties of the Gauss transformation are worked out by Cornfeld, Fomin and Sinai [30, pp. 165–177, Chapter 7, §4], as an instance of piecewise monotonic transformations.

For each we define by . For example, , and it is known [92, p. 74, Theorem 2] that for ,

The pattern for the continued fraction expansion of seems first to have been worked out by Roger Cotes in 1714 [50], and was later proved by Euler using a method involving the Riccati equation [31].

Theorem 3.

Let , , and for , , ,

and

Then

It follows from the above that for , ,

5 Diophantine conditions

For real let

and let

We relate the sets and continued fractions expansions [101, p. 241, Lemma C.6], cf. [158, p. 130, Proposition 2.4].

Lemma 4.

For and , if and only if there is some such that for all .

Proof.

For a positive integer, let

so is the set of those with bounded partial quotients.

Lemma 5.

For , if and only if .

Proof.

Write and . If then there is some such that , hence for ,

Now, for , so

which shows that has bounded partial quotients.

A complex number is called an algebraic number of degree , , if there is some polynomial with degree such that and if has degree and then . An algebraic number number of degree is called a quadratic irrational. Let . It was proved by Euler [59, p. 144, Theorem 176] that if there is some and some such that for all then is a quadratic irrational The converse of this was proved by Lagrange [59, p. 144, Theorem 177], namely that a quadratic irrational has eventually periodic partial quotients. For example, is a quadratic irrational, being a root of , and one works out that , and that for . In particular, if is a quadratic irrational, then has bounded partial quotients.

6 Sums of reciprocals

We are interested in getting bounds on the sum . This is an appealing question because the terms are unbounded.

Rather than merely stating that , we give more information by giving the estimate

where is Euler’s constant. Likewise, rather than merely stating that there are infinitely many primes, we state more information with [90, p. 102, §28]

for a certain constant (namely “Merten’s constant”), or with [90, p. 226, §61]

Because and

we have

| (14) |

Thus, getting bounds on will give us bounds on .

Let be a nondecreasing function defined on the positive integers such that for (for example, ). Following Kuipers and Niederreiter [85, p. 121, Definition 3.3], we say that an irrational number is of type if for all integers . If is a constant function, then we say that is of constant type.

Lemma 6.

is of constant type if and only if it has bounded partial quotients.

Proof.

Suppose that is of constant type. So there is some such that for all integers . For we have , and hence, by (11),

showing that has bounded partial quotients.

However, almost all do not have bounded partial quotients [78, p. 60, Theorem 29]. Shallit [134] gives a survey on numbers with bounded partial quotients.

We state and prove a result of Khinchin’s [78, p. 69, Theorem 32] that we then use.

Lemma 7.

Let be a positive function on the positive integers. If

then for almost all there are only finitely many such that .

Proof.

For each positive integer , let . If , then there is some integer with such that . It follows that

Therefore

Let , i.e. . Then by the Borel-Cantelli lemma [19, p. 59, Theorem 4.3] we have that . Therefore, for almost all there are only finitely many such that , i.e., for almost all there are only finitely many such that . ∎

The above lemma is proved in Benedetto and Czaja [15, p. 183, Theorem 4.3.3] using the fact that a function of bounded variation is differentiable almost everywhere. We outline the proof. Define by if , , , and if . Writing , for ,

It follows that the total variation of is and hence is a function of bounded variation. Because has bounded variation, the set of at which is differentiable is a Borel set with . Check that for , and using this, if with and then for some , if then .

We use the above lemma to prove the following result.

Lemma 8.

Let . For almost all , there is some such that is of type .

Proof.

Let

Since converges, we have by Lemma 7 that . Let . Then for all sufficiently large . It follows that there is some such that is of type . ∎

The following technical lemma is from Kuipers and Niederreiter [85, p. 130, Exercise 3.9]; cf. Lang [92, p. 39, Lemma].

Lemma 9.

Let be of type . If and if , then

Proof.

Since and are relatively prime, the remainders of , , when divided by are all distinct. Then also, the remainders of , , when divided by are all distinct. Let , , be the remainder of when divided by . We have ; let , , and .

Write ; by (11) we have . If then by Theorem 2 we have , and since is of type we have

Let, for ,

If and , then

It follows that

But for , so

the last inequality is because, for all ,

∎

We now use Lemma 9 to obtain a bound on in terms of the type of . This is from Kuipers and Niederreiter [85, p. 131, Exercise 3.11]; cf. Lang [92, p. 39, Theorem 2].

Theorem 10.

If is of type , then for all we have

Proof.

We shall prove the claim by induction. Because is of type , we have

so the claim is true for . Take and assume that the claim is true for all . We shall show that it is true for .

Let . Either or . In the first case, using Lemma 9 we have

In the second case, using the induction assumption (with ) and Lemma 9 we have, because ,

The claim is true in both cases, which completes the proof by induction. ∎

We can now establish for almost all a tractable upper bound on the sum , and thus by (14) also on ; cf. Lang [92, p. 44, Theorem 3].

Theorem 11.

Let . For almost all , we have

while if has bounded partial quotients then

Proof.

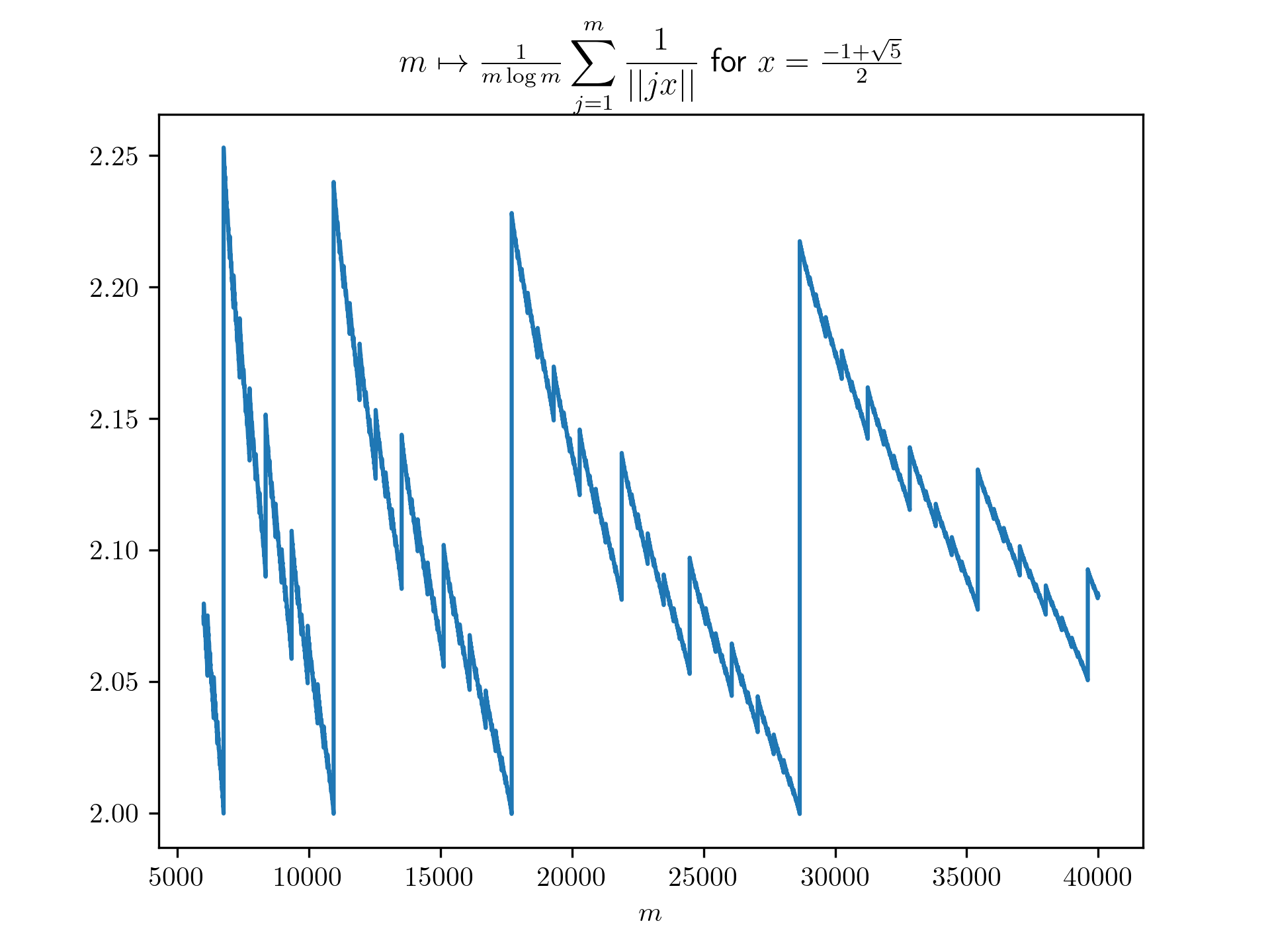

For example, take , for which for all , and so in particular has bounded partial quotients. In Figure 1 we plot for . These computations suggest that there is some constant for which for all . In Theorem 13 we shall prove that for almost all there is such a .

However, the estimate in Theorem 11 is not true for all . Define as follows. Let be any element of . Then inductively, define to be any element of that is . Then for any , using (11) and we get

hence , and then

Using , it is then straightforward to check that there is no constant such that for all .

We will need the following lemma [19, p. 324, Lemma 3] to prove a theorem; cf. Khinchin [78, p. 63, Theorem 30].

Lemma 12.

If is a function defined on the positive integers such that for all and

then for almost all there are only finitely many such that .

Proof.

For a measurable set , define

in other words . Thus for a measurable set we have

and

We will use that is an invariant measure for the Gauss transformation [44, p. 77, Lemma 3.5], i.e., if is a measurable set then

Let , . As

we have

Hence

Let be Lebesgue measure on , let , and let be the Gauss transformation, for and , for which [44, p. 77, Lemma 3.5]. Suppose that is a Borel probability measure on such that the pushforward measure is absolutely continuous with respect to . For , define , and define by

Thus, for , using the change of variables formula,

in particular,

We call a Perron-Frobenius operator for . It is a fact that if then [69, p. 57, Proposition 2.1.1], namely . It can be proved that for , for almost all [69, p. 59, Proposition 2.1.2],

and for , for almost all [69, p. 60, Corollary 2.1.4],

and with , for it holds for almost all that . Iosifescu and Kraaikamp [69, Chapter 2] give a detailed presentation of Perron-Frobenius operators for the Gauss map. We make the final remark that is equivalent with for all Borel sets in , i.e. , which in turn means , cf. Markov operators [83, Chapter 5, §5.1, pp. 177-186]. An object similar to Perron-Frobenius operators for the Gauss transformation is the zeta-function for the Gauss transformation, for which see Lagarias [87, p. 58, §3.3].

The following theorem gives a lower bound on the sum , cf. [150, p. 4, Theorem 3.1].

Theorem 13.

For almost all there is some such that

Proof.

For all , if then , by (9). Take . The series converges, so by Lemma 12, for almost all there are only finitely many such that . That is, for almost all there is some such that if then

Hence, if then

It follows that for almost all there is some such that

| (15) |

for all .

For such an , let be a positive integer and let . For we have by (11),

Therefore for we have

Let , so . Then,

The following is from Kuipers and Niederreiter [85, p. 131, Exercise 3.12].

Theorem 14.

If is of type , then for all we have

Proof.

Summation by parts is the following identity, which can be easily checked:

Let , let , let , and let for . Doing summation by parts gives

As is of type , we can use Theorem 10 to get for each . Therefore

∎

Erdős [45] proves that for almost all ,

Kruse [84] gives a comprehensive investigation of the sums , . The results depend on whether and are are less than, equal, or greater than , and on whether . One of the theorems proved by Kruse is the following [84, p. 260, Theorem 7]. If and , and if , then for almost all we have

Haber and Osgood [56, p. 387, Theorem 1] prove that for real , , , , there is some such that for all satisfying , for all positive integers ,

We remind ourselves that according to Theorem 4, the elements of are those for which there is some such that for all .

For , define . If , then there is an integer for which for all integers , and we define . Sinai and Ulcigrai [138, p. 96, Proposition 2] prove that if has bounded partial quotients, then there is some such that for all ,

7 Weyl’s inequality, Vinogradov’s estimate, Farey fractions, and the circle method

Write

We first prove four estimates following Nathanson [107, pp. 104–110, Lemmas 4.8–4.11] that we will use in what follows; cf. Vinogradov [149, p. 26, Chapter I, Lemma 8b].

Lemma 15.

There is some such that if , , and

then

Proof.

For , . For , let . As and , . So for , there is some such that . Then

Put , so (i) or (ii) . In case (i), . In case (ii), . In case (i) let , and in case (ii) let . Thus, whether (i) or (ii) holds we have

Write

for some real , . For , which satisfies ,

Then

Take and suppose that . So

hence . As , . Because , if then and if then and , so in any case . Therefore

Using the two things we have established,

∎

Lemma 16.

There is some such that if , , and

then for any positive real and nonnegative integer ,

Proof.

Write

which satisfies , and for define

which satisfies . Then

For ,

Suppose that and that . Then

This implies, as ,

and, as ,

so , writing

For , if then , and implies ; and so . For , four integers belong to , hence

has at most four elements. But

Now,

whence

This shows that if then

has at most eight elements. For , writing

the set has at most eight elements. Therefore

∎

Lemma 17.

There is some such that if , ,

is a real number, and is a positive integer, then

Proof.

Lemma 18.

There is some such that if , ,

and are real numbers, then

Weyl’s inequality [107, p. 114, Theorem 4.3] is the following. For and , there is some such that if , is a real polynomial with highest degree term , , and

then, writing and ,

Weyl’s inequality is proved using Lemma 18.

Montgomery [103, Chapter 3] gives a similar but more streamlined presentation of Weyl’s inequality. Chandrasekharan [29] gives a historical survey of exponential sums.

Vinogradov’s estimate [146, p. 26, Theorem 3.1] states that there is some such that for , , , and , then

| (16) |

where ; cf. Nathanson [107, p. 220, Theorem 8.5] and Vinogradov [149, p. 131, Chapter IX, Theorem 1]. This is proved using Lemma 17.

Fix and let . For and , let

called a major arc. One checks that there is some such that if , then and are disjoint when . Let

The Farey fractions of order are

Cf. the Stern-Brocot tree [55, §4.5]. For early appearances of Farey fractions, see Dickson [35, pp. 155–158, Chapter V]. It is proved by Cauchy that if and are successive elements of , then [59, p. 23, Theorem 28]. Let

the Euler phi function, and write . One sees that , and it was proved by Mertens [59, p. 268] that

Let be Lebesgue measure on . For , because the major arcs are pairwise disjoint,

Let , which for contains . Let

called the minor arcs.

With and

we have

Using (16), it can be proved that for with [146, p. 29, Theorem 3.2],

Writing

called the singular series, it is proved, using the Siegel-Walfisz theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions [102, p. 381, Corollary 11.19], that for with [146, p. 31, Theorem 3.3],

Thus

and it follows from this that there is some such that if is odd then there are primes such that .

For integers with , the Ford circle is the circle in that touches the line at and has radius ; in other words, is the circle in with center and radius . It is straightforward to prove that if and are Ford circles, then they are tangent if and only if , and otherwise they are disjoint [4, p. 100, Theorem 5.6]. It is also straightforward to prove [4, p. 101, Theorem 5.7] that if are successive elements of , then and touch at

and and touch at

Bonahon [21, pp. 207 ff., Chapter 8] explains Ford circles in the language of hyperbolic geometry.

We remind ourselves that and let be the elements of . In particular, and . For with , write .

Let be the clockwise arc of from to the point at which and touch. For , let be the clockwise arc of from the point at which and touch to the point at which and touch. Finally, let be the clockwise arc of from the point at which and touch to . Let be the composition of the arcs

| (17) |

which is a contour from to .

Write . The Dedekind eta function is defined by

It is straightforward to check that is analytic and that for all [143, pp. 17–18, §1.44]. For , let

called a Dedekind sum; is the periodic Bernoulli function. Also, for write

The functional equation for the Dedekind eta function [4, p. 52, Theorem 3.4] is

Let be the number of ways of writing as a sum of positive integers where the order does not matter, called the partition function. For example, are the partitions of , so . Denoting by the open disc with center and radius , define by

that the product and the series are equal was found by Euler. is analytic. On the one hand, , and on the other hand, by Cauchy’s integral formula [143, p. 82, Theorem 2.41], if is a circle with center and radius then

Taking to be the circle with center and radius and doing the change of variable ,

where we remind ourselves that is the contour (17) from to . Using this and the functional equation for the Dedekind eta function, Rademacher [4, p. 104, Theorem 5.10] proves that for ,

for .

8 Discrepancy and exponential sums

Discrepancy and Diophantine approximation are covered by Kuipers and Niederreiter [85, Chapters 1–2 ] and by Drmota and Tichy [41, §§1.1–1.4], especially [41, pp. 48–66, §1.4.1].

Let , , be a sequence of real numbers, and let . For a positive integer , let be the number of , , such that . We say that the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo if we have for all and with that

It can be shown [85, p. 3, Corollary 1.1] that a sequence is uniformly distributed modulo if and only if for every Riemann integrable function we have

| (18) |

Thus, if a sequence is uniformly distributed then the integral of any Riemann integrable function on can be approximated by sampling according to this sequence. This approximation can be quantified using the notion of discrepancy.

It can be proved [85, p. 7, Theorem 2.1] that a sequence is uniformly distributed modulo if and only if for all nonzero integers we have

this is called Weyl’s criterion. But if , then

| (19) |

We thus obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 19.

If then the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo .

The discrepancy of a sequence is defined, for a positive integer, by

One proves that the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo if and only if as [85, p. 89, Theorem 1.1].

For , let denote the total variation of . Koksma’s inequality [85, p. 143, Theorem 5.1] states that for any sequence , for any of bounded variation, and for any positive integer , we have

| (20) |

Following Kuipers and Niederreiter [85, p. 122, Lemma 3.2], we can bound the discrepancy of the sequence in terms of the sum on the left-hand side of Theorem 14

Lemma 20.

There is some such that for all , , and for all positive integers we have

Proof.

We shall use the following inequality, which lets us bound the discrepancy of a sequence in terms of exponential sums formed from the elements of the sequence. The Erdős-Turán theorem [85, p. 114, Eq. 2.42] states that there is some constant such that for any sequence of real numbers, any positive integer , and any positive integer we have

| (21) |

It follows from Theorem 14 and Lemma 20 (taking ) that if is of type then

| (22) |

Lemma 8 tells us that for almost all there is some such that is of type , so for almost all , the bound (22) is true. It likewise follows that if has bounded partial quotients then

| (23) |

In fact, it can be proved that if then, for [85, p. 125, Theorem 3.4],

We use the above bounds in the proof of the following theorem.

Theorem 21.

Let . For almost all we have

while if has bounded partial quotients then

Proof.

Like we mentioned at the beginning of §6, because and , we have

Thus Theorem 21 also gives estimates for .

We can investigate the sum rather than ; see Lang [92, p. 37, Theorem 1], who proves that for almost all ,

For , let , the denominator of the th convergent of the continued fraction expansion of , and let , the th partial quotient of the continued fraction expansion of . For , one can prove [18, p. 211, Proposition 1] that can be written in one and only one way in the form

| (24) |

where (i) , (ii) for , (iii) for , if then , and (iv) and for . The expression (24) is called the Ostrowski expansion of . We emphasize that this expansion depends on . Berthé [18] surveys applications of this numeration system in combinatorics. For , define and . Brown and Shiue [24, p. 184, Theorem 1] prove that for ,

| (25) |

where and if then . If , then by (11) we have . For , using the fact that (for the same reason that if the highest power of appearing in a number’s binary expansion is , then the number is ),

Using (25), this inequality, and the inequality , we obtain

If the continued fraction expansion of has bounded partial quotients, say for all , we obtain from the above that

It can be proved [24, p. 185, Fact 2] that . Thus, if for all , then for ,

This is Lerch’s claim stated in §3. For example, if then for all . We compute that

on the other hand, we compute that

Brown and Shiue [24, p. 185, Fact 1] use (25) to obtain the result of Sierpinski stated in §3 that for all ,

They also prove [24, p. 188, Theorem 4] that for , there exists some such that for , if there are infinitely many such that (which happens in particular if has bounded partial quotients), then there are infinitely many such that

and there are infinitely many such that

It can be shown [92, p. 44, Theorem 4] that if is a positive integer and , then for almost all we have

Lang attributes this result to Vinogradov. But it is not so easy to obtain a bound on this exponential sum for specific . For , one can prove [92, p. 45, Lemma] that for any ,

cf. Steele [142, Problem 14.2]. By (14) this gives us

If has bounded partial quotients, it follows from Theorem 11 that

Hardy and Littlewood [57, p. 28, Theorem B5] prove that if is an algebraic number, then there is some such that . Pillai [115] gives a different proof of this.

Theorem 22 (Hardy and Littlewood, Pillai).

For , if then for ,

Pillai [114] proves other identities and inequalities for , some for all and some for all algebraic .

For , and for , we remind ourselves that denotes the number of , , such that . Define for ,

It is straightforward to prove that [85, p. 91, Theorem 1.3]. For write . Let and let . Suppose that and

For denote by the number of primes such that . Vinogradov [149, p. 177, Chapter XI, Theorem] proves that for ,

Let , , where is the th prime. Using Vinogradov’s estimate, one proves that for , as , which implies that the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo . A clean proof of this is given by Pollicott [116, p. 200, Theorem 1], and this is also proved by Vaaler [145] using a Tauberian theorem. See also the early survey by Hua [68, pp. 98–99, §38].

Defining , Beck [11, p. 14, Theorem 3.1] proves that there is some such that for every ,

as . Beck [12, p. 20, Theorem 1.2] further proves that if is a quadratic irrational, there are and such that for , ,

Beck and Chen [10]

9 Dirichlet series

The result of de la Vallée-Poussin [34] stated in §3 implies that there is no such that for all irrational the Dirichlet series converges. It follows from this fact that there is no such that for all irrational the Dirichlet series converges.

Lerch [97] in 1904 gives some statements without proof about the series

He states that if is a real algebraic number that does not belong to , then for sufficiently large this series converges, and states, for example, that with ,

Writing , Berndt [17, p. 135, Theorem 5.1] proves that if is a real algebraic number of degree and (to say that is to say that is irrational), then converges.

For a Dirichlet series , one can show [143, pp. 289–290, §9.11] that if the series is convergent at , then for and any the series is convergent at . It follows that there is some such if then the series diverges at , and if then the series converges at . We call the abscissa of convergence of the Dirichlet series. If each is a nonnegative real number, then the function

cannot be analytically continued to any domain that includes [67, p. 101, Proposition 18].

Let be a sequence of complex numbers. It can be shown [143, pp. 292–293, §9.14] that if and the sequence diverges, then the abscissa of convergence of the Dirichlet series is given by

By Theorem 11 and Theorem 13 (taking, say, ), for almost all there are such that for all positive integers we have

Thus, if , then

and hence

It follows that for almost all the abscissa of convergence of the Dirichlet series is .

Likewise, by Theorem 21 (taking ), we get for almost all that . We can then check that , and hence that the abscissa of convergence of the Dirichlet series is .

A 1953 result of Mahler [48, pp. 107–108] implies that if is an algebraic number of degree , then, for , the Dirichlet series

has abscissa of convergence , and the power series

has radius of convergence 1.

Rivoal [126] presents later work on similar Dirichlet series. See also Queffélec and Queffélec [120]. Lalín, Rodrigue and Rogers [88] prove results about Dirichlet series of the form . Duke and Imamoḡlu [42] review Hardy and Littlewood’s work on estimating lattice points in triangles, and prove results about lattice points in cones.

10 Power series

For a power series with radius of convergence , the Cauchy-Hadamard formula [124, p. 111, Chapter 4, §1] states

| (26) |

The radius of convergence is equal to the supremum of those for which is a bounded sequence.

Lemma 23.

If , then the power series

and

have the same radius of convergence.

Proof.

The radii of convergence of these power series are respectively

On the one hand,

Therefore, since ,

On the other hand, since for ,

Therefore, using , we have

showing that the two power series have the same radius of convergence. ∎

We show in the following theorem that for almost all , the power series has radius of convergence .

Theorem 24.

For almost all , the power series

| (27) |

has radius of convergence .

Proof.

For , let be the radius of convergence of the power series (27). We have , so . Therefore as , and so the power series (27) diverges at . Therefore for all .

We shall use Lemma 7 to get a lower bound on that holds for almost all . Let , let , and let be those such that infinitely often. If , then , and this implies that there are infinitely many such that , so , i.e. . But let . Then converges, since , so, by Lemma 7, for almost all there are only finitely many such that . Thus . Hence , and since we get that

that is, for almost all . In conclusion, for almost all . ∎

In fact, we can prove the above theorem using the bounds we obtained in Theorem 11. By Theorem 11, for almost all we have that . (Here we will merely need the fact that the sum is subexponential in .) For such an , take . Let , let , let , and let for . Using summation by parts, namely

we get

Therefore

Since is increasing in (being a sum of positive terms), we obtain that the series converges. Since this is true for all with , it follows that .

For let be the radius of convergence of the power series . We proved in Theorem 27 that for almost all , .

Theorem 25.

For , let be the radius of convergence of the power series , and let and . Then

For any there is some such that .

Proof.

From the Cauchy-Hadamard formula (26),

Then . On the one hand, by (11), , and hence , and using that ,

On the other hand, let and take . Applying (12),

Then applying Theorem 2, and using that and ,

As as , this implies

For , let for . Define as follows. Define . Suppose for that we have defined and thus and . Define . Then , so . Therefore for , . Now, so . Then , hence

We have therefore established that when , .

For , define by and , which satisfies . For ,

For , define by for all . Namely, . For it is immediate that . ∎

Since , of course the power series has radius of convergence . The following result, for which Pólya and Szegő [117, p. 280, Part II, No. 168] cite Hecke, shows in particular that the radius of convergence of this power series is for and is thus equal to .

Theorem 26.

For , let

We have

Proof.

Since , the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo . Therefore, with we have by (18) that

We will use the following result [117, p. 21, Part I, No. 88]. If a sequence of complex numbers satisfies , then

Let , and we thus have

∎

It follows from the above theorem that if then is a natural boundary of the function defined on the open unit disc by ; cf. Segal [133, p. 255, Chapter 6], who writes about this power series, and who gives a thorough introduction to natural boundaries in the same chapter. Breur and Simon [22] prove a generalization of this result.

Hata [62, p. 173, Problem 12.6] mentions the appearance of the function from the above theorem in the study of the Caianiello neuron equations.

11 Product

We will use the following lemma proved by Hardy and Littlewood [58, p. 89], whose brief proof we expand.

Lemma 27.

Let be positive and nondecreasing. If

then for almost all , there exists some such that for all and for all real , there are at most integers that satisfy .

Proof.

By Lemma 7, for almost all there is some such that if then

| (28) |

Let be large enough so that

also let . Now suppose by contradiction that there is some and some such that there are more than integers that satisfy . Then there are some satisfying and and such that

so . On the other hand,

so . Thus , i.e.,

because and . Moreover, since , we have . This contradicts (28). ∎

Hardy and Littlewood [58, p. 89, Theorem 4] prove the following theorem that gives us the conclusion (18) for certain functions that are not Riemann integrable on .

Theorem 28.

Let be nonnegative, let be nonincreasing on and nondecreasing on , and let

Let be a positive and nondecreasing function such that

If

then for almost all ,

Proof.

For , define

From Lemma 27, for almost all there is some such that for all and there are at most integers satisfying . Let

where

and

There are at most integers that satisfy , thus, as is nondecreasing, there are at most terms in . For each term in , since we have, by assumption on , either or , and hence

Therefore,

Let . Because , there exists a such that if then .

On the other hand, since is Riemann integrable on and because, by (19), the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo , we obtain from (18) that

As , there exists a such that for and for sufficiently large ,

Therefore, for sufficiently large and for sufficiently small ,

Thus for sufficiently large ,

∎

By the Birkhoff ergodic theorem [44, p. 44, Theorem 2.30], if and , then for almost all ,

This equality holding for is the conclusion of Theorem 28.

Baxa [9] reviews further results that give conditions when a function that is not Riemann integrable on nevertheless satisfies

for certain . Oskolkov [109, p. 170, Theorem 1] shows that if satisfies and , and also the improper Riemann integral of on exists, then, for ,

if and only if

where is the denominator of the th convergent of the continued fraction expansion of .

Driver, Lubinsky, Petruska and Sarnak [40]

Using Theorem 28 we can now prove the following theorem of Hardy and Littlewood [58, p. 88, Theorem 2].

Theorem 29.

For almost all ,

Proof.

Let . Using and , one can check that . (The earliest evaluation of this integral of which we are aware is by Euler [46], who gives two derivations, the first using the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula, the power series expansion for , and the power series expansion of , and the second using the Fourier series of .) Thus, . So satisfies the conditions of Theorem 28.

Let . First, upper bounding the series by an integral,

Second,

Therefore by Theorem 28, for almost all ,

i.e.

∎

Hardy and Littlewood give another proof [58, p. 86, Theorem 1] of the above theorem, which we now work out. This proof is complicated and we greatly expand on the abbreviated presentation of Hardy and Littlewood.

We remind ourselves that the Cauchy-Hadamard formula states that the radius of convergence of a power series satisfies

Theorem 30.

Fix and write . Let and respectively be the radii of convergence of the power series

Then , and if then .

The functions and are analytic [143, p. 69, Theorem 2.16].

Using the Cauchy-Hadamard formula we have

and

| (29) |

Lemma 31.

For and for ,

Proof.

Because we have . Hence , from which the claim follows. ∎

We assert the following as a common fact in complex analysis.

Lemma 32.

For define

If , then .

For , we define

For , define and for ,

and thus for ,

Furthermore define and for ,

and thus for ,

For , define and for ,

and thus for ,

Furthermore define and for ,

and thus for ,

We prove directly the following, which is an instance of the -binomial formula [3, p. 17, Theorem 2.1].

Proposition 33.

If then

Proof.

By Lemma 32,

Because for ,

Define

On the one hand, . On the other hand,

thus

and therefore for we have . Thus by induction, for ,

Hence

∎

Proposition 34.

, and if then .

Proof.

If then the claim is immediate. Otherwise, . Let , , and define . On the one hand,

which implies that for and for . On the other hand, for , using Proposition 33,

By Lemma 31,

and because it is the case that . Then for ,

as , and therefore

Now fix , take such that , and write and . Because ,

which implies that . Therefore . Furthermore, because

by the Weierstrass -test [128, p. 148, Theorem 7.10], the sequence converges uniformly for and therefore [128, p. 149, Theorem 7.11]

Now, for , by Lemma 31,

Because , the series converges, and therefore by the Weierstrass -test, the sequence converges uniformly for . Then

Then using Lemma 33,

completing the proof. ∎

Lemma 35.

If and then

Proof.

∎

Lemma 36.

Let , let , and suppose that there is some such that for all . Then

Proof.

Take and let

Thus if and then . Write . Because ,

Because is irrational, by Theorem 19 the sequence is uniformly distributed modulo . Therefore

and this implies

Because this is true for each it follows that , proving the claim. ∎

Proposition 37.

.

Proof.

We have found in (29) that , i.e. . Assume by contradiction that ; in particular , which implies . By Proposition 34, we have for and so for .

Let be the distinct zeros of on , with respective multiplicities ; if there is none, take , and use and . Define

Because is analytic and for , there is some , , such that for [129, p. 208, Theorem 10.18]. As is simply connected, there is an analytic function such that for [129, p. 274, Theorem 13.11]. Thus

For we have , and then by Lemma 32, . Therefore for ,

i.e.

But the image of a continuous function is connected, and because has the discrete topology it follows that the image is a singleton, thus there is some such that

But , so , and , hence . Therefore

Now, for ,

Let . For ,

so for ,

Then

| (30) |

Cauchy’s integral formula [143, p. 82, Theorem 2.41] tells us that for , , ,

whence, as the length of is ,

Fix , with which

and for we have

Using this and

(30) yields

As

we get

For any , there is some such that , and thus the above estimate is contradicted if ; hence . (We emphasize that is deduced from the assumption , which we are showing to imply a contradiction.) By Lemma 36 we then get that

| (31) |

Now, multiplying each side of (30) by its complex conjugate and using that and that ,

i.e.

| (32) |

Let and let . Then summing (32) for , using ,

Because for , we have according to Lemma 35 that

Thus

and because this contradicts (31). Therefore, it is false that , which means that , proving the claim. ∎

Theorem 38.

Let and let and respectively be the radii of convergence of the power series

Then .

Proof.

By Lemma 23 and Theorem 24, for almost all , the power series has radius of convergence . Then using Theorem 38, for almost all the power series has radius of convergence , and thus for almost all ,

Hardy and Littlewood give a separate argument [58, p. 88, Eq. 4.3] proving that for almost all ,

and combining the formulas for the limit inferior and limit superior yields Theorem 29.

Lubinsky [98] proves more results about products of the form . For example, Lubinsky [98, p. 219, Theorem 1.1] proves that for all , for almost all we have

The author [14, p. 532, Theorem 2] gives asymptotic expressions for the norm of as , for .

For let . Let be the th Fibonacci number and let . Verschueren and Mestel [148, p. 204, Theorem 2.2] prove that there is some such that

and

and that there are and such that for all ,

Let be a measure space with probability measure . Following [137, p. 21, Definition 3.6], we say that a measure preserving map is -fold mixing if for all we have

| (33) |

If for each the map is -fold mixing, we say that is mixing of all orders.

Let be an integer, and define by . We assert that is mixing of all orders. This can be proved by first showing that the dynamical system is isomorphic to a Bernoulli shift (cf. [44, p. 17, Example 2.8]). This implies that if the Bernoulli shift is -fold mixing then is -fold mixing. One then shows that a Bernoulli shift is mixing of all orders [44, p. 53, Exercise 2.7.9]. Using that is mixing of all orders gets us the following result.

Theorem 39.

Let be an integer. For each we have

Proof.

See Sinai [136].

Write , where and . Knill and Tangerman [79] talk about motivations from KAM theory for caring about these sums. See Lagarias [86] and Ghys [54] for more on small divisors in Hamiltonian dynamics, and Carleson and Gamelin [26, p. 48, Theorem 7.2] and Yoccoz [158] for Arnold’s theorem on analytic circle diffeomorphisms.

Marmi and Sauzin [99]

12 Conclusions

Kac and Salem [73] prove the following. Let be a sequence of nonnegative real numbers for which . If the series

converges in a set of positive measure, then

and if this condition is satisfied then converges for almost all .

Muromskii [105, p. 54, Theorem 1] proves that if is a sequence of nonnegative real numbers, if , and if there is a set of positive measure on which the series

converges, then for any , the series

converges.

Let be a random variable that is uniformly distributed on . Kesten [77, p. 111, Theorem 1 ] proves that if , then the series

converges with probability . Stated using measure theory, the conclusion is that for almost all , the series

converges. Kesten [77, p. 114, Theorem 3] also proves if and , then

in probability. Stated using measure theory, the conclusion is that for each ,

For , let be Haar measure on and let be Haar measure on , with . A sequence , , is said to be uniformly distributed if for any arcs in , with ,

Kronecker’s approximation theorem [144, p. 108, Theorem 6.3] states that if and is linearly independent over , then the sequence , , is uniformly distributed in . Meyer [100] is a thorough presentation of multidimensional Diophantine approximation and Diophantine approximation with locally compact abelian groups, and harmonic analysis involving sets satisfying various Diophantine properties.

Measure theoretic results in Diophantine approximation are presented in Khinchin [78], Einsiedler and Ward [44, Chapter 3], Rockett and Szüsz [127, Chapters V and VI], Billingsley [19, pp. 13–15, 319–326], Kac [74, Chapter 5], Bugeaud [25], and Kesseböhmer, Munday and Stratmann [76]. The significance of continued fraction expansions of irrational numbers in the early history of axiomatic probability theory is described by Barone and Novikoff [8], Durand and Mazliak [43], and von Plato [151]. Veech [147] presents material on Diophantine approximation in the setting of topological dynamics.

We have been interested in results about almost all , using Lebesgue measure on . If has , one can ask what the Hausdorff dimension of the set is. Let be the set of those such that for all , and let , the set of those with bounded partial quotients. We have already stated that [78, p. 60, Theorem 29], and Jarník [39, Theorem 4.3] proves that the Hausdorff dimension of is in fact 1; cf. Falconer [47, p. 155, Theorem 10.3] and Wolff [157, p. 67, Chapter 9] on Hausdorff dimension. Hensley [64] proves

Dodson and Kristensen [39] give a survey of results on the Hausdorff dimension of various sets that appear in Diophantine approximation.

For a decreasing positive function , the set

can be written as the limsup of a sequence of sets,

where

One can exploit nice properties of limsup sets, such as the Borel-Cantelli lemma and invariance under ergodic transformations, to prove fundamental results in Diophantine approximation. Beresnevich, Dickinson and Velani [16] use this motiviation of Diophantine approximation to build a framework for a natural class of limsup sets on compact metric spaces. Their general results readily imply the divergent case of Khinchin’s theorem: if (Lemma 7) and if . Their framework also establishes the divergent case of Jarník’s theorem: the -Hausdorff dimension of is if and is infinity if , where is a dimension function such that as , and is decreasing.

As well, rather than making statements about subsets of of measure , we can talk about sets whose complements are meager. (Measure theoretically, the notion of a negligible set is made precise as a set of measure , and topologically the notion of a negligible set is made precise as a meager set.) Some results of this type are proved in Oxtoby [111, Chapter 2].

Let be prime, let , and let be the -adic numbers. For let

and let , the -adic integers. Let be the Haar measure on the additive locally compact abelian group with . We call a -adic Liouville number if , and let be the set of -adic Liouville numbers. One checks that if then [130, p. 201, Exercise 66.A]. It can be proved that is a dense set in [130, p. 204, Theorem 67.3] and that [130, p. 205, Theorem 67.4]. One reason for caring about -adic Liouville numbers is that if is algebraic over then , and hence a -adic Liouville number is transcendental over [130, p. 203, Theorem 67.2].

Unlike in estimating exponential sums, the sums that we have been estimating in this paper do not have cancellation. Instead we have estimated them by showing that the terms are only occasionally large. For , it can be proved [118, p. 74, no. 25] that

On the other hand, let be the maximum of . It can be proved [118, p. 77, no. 38] that

Walfisz [152] presents results of his, of Oppenheim, and of Chowla on sums

for , the number of ways to write as a sum of squares, and for , the number of positive divisors of . One of the results of Chowla is that if has bounded partial quotients, then

One of the results Walfisz proves is that if , then for almost all ,

Wilton [156] proves some similar results. For example, Wilton proves that for any ,

See Jutila’s book on exponential sums [72].

Let for and for , where is a periodic Bernoulli function. Namely, for all ,

Define , where is the Möbius function. Davenport [33, p. 11, Theorem 2] proves that there is some such that for all and for all ,

Davenport [33, p. 13, Theorem 4] also proves that for almost all ,

See Jaffard [70].

It would be a useful project to give an organized presentation of Hardy and Littlewood’s results on Diophantine approximation. Their papers in this area are all included in Hardy’s collected works [61]. Hardy and Littlewood proved many pleasant results on various sums and series with coefficients related to and . It would be desirable to streamline and systematically prove these results, to let a modern reader to be able to understand them without having to read the whole series of papers to figure out what results are being tacitly used from earlier work or assumed as general knowledge. There is only a bare summary of Hardy and Littlewood’s work in the commentary in Hardy’s collected papers. Hardy’s work on Diophantine approximation is briefly summarized by Mordell [104]. See also lecture V of Hardy’s lectures on Ramanujan [60].

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Hervé Queffélec (Université de Lille) and Martine Queffelec (Université de Lille) for a long correspondence on Hardy and Littlewood’s “curious power-series” [58].

The author thanks Jeremy Voltz (University of Toronto) for discussions on Beresnevich, Dickinson and Velani’s monograph [16] on limsup sets.

References

- [1] (2008) Foundations of mechanics. Second edition, AMS Chelsea Publishing, Providence, Rhode Island. Cited by: §12.

- [2] (2006) Infinite dimensional analysis: a hitchhiker’s guide. third edition, Springer. Cited by: §4.

- [3] (1976) The theory of partitions. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications, Vol. 2, Addison-Wesley. Cited by: §11.

- [4] (1990) Modular forms and Dirichlet series in number theory. second edition, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Vol. 41, Springer. Cited by: §7, §7, §7.

- [5] (1981) Les recherches de M. Fréchet, P. Alexandrov, W. Sierpinski et K. Kuratowski sur la théorie des types de dimensions et les débuts de la topologie générale. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 24 (4), pp. 339–388. Cited by: §4.

- [6] (1898–1904) Analytische Zahlentheorie. In Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften mit Einschluss ihrer Anwendungen, Band I, 1. Teil, W. F. Meyer (Ed.), pp. 636–674. Cited by: §3.

- [7] (1922–1933) Über Gauss’ zahlentheoretische Arbeiten. In Carl Friedrich Gauss Werke, Band 10, Abteilung 2, G. der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen (Ed.), pp. 1–74. Cited by: §3.

- [8] (1978) A history of the axiomatic formulation of probability from Borel to Kolmogorov: part I. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 18 (2), pp. 123–190. Cited by: §12.

- [9] (2005) Calculation of improper integrals using uniformly distributed sequences. Acta Arith. 119 (4), pp. 373–406. External Links: ISSN 0065-1036, Document, Link, MathReview (Michael Drmota) Cited by: §11.

- [10] (1987) Irregularities of distribution. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, Cambridge University Press. Cited by: §8.

- [11] (1998) From probabilistic Diophantine approximation to quadratic fields. In Random and Quasi-Random Point Sets, P. Hellekalek and G. Larcher (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Statistics, Vol. 138, pp. 1–48. Cited by: §8.

- [12] (2014) Probabilistic Diophantine approximation: randomness in lattice point counting. Springer. Cited by: §8.

- [13] (1924) Zur Theorie der diophantischen Approximationen. Abhandlungen aus dem mathematischen Seminar der Hamburgischen Universität 3, pp. 261–318. Cited by: §3.

- [14] (2013) Estimates for the norms of products of sines and cosines. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 405 (2), pp. 530–545. Cited by: §11.

- [15] (2009) Integration and modern analysis. Birkhäuser Advanced Texts, Birkhäuser. Cited by: §6.

- [16] (2006) Measure theoretic laws for lim sup sets. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI. Cited by: §12, Acknowledgments.

- [17] (1976) Dedekind sums and a paper of G. H. Hardy. J. London Math. Soc. (2) 13 (1), pp. 129–137. Cited by: §9.

- [18] (2001) Autour du système de numération d’Ostrowski. Bull. Belg. Math. Soc. Simon Stevin 8 (2), pp. 209–239. External Links: ISSN 1370-1444, Link, MathReview (Jean-Paul Allouche) Cited by: §8.

- [19] (1995) Probability and measure. third edition, John Wiley & Sons. Cited by: §12, §6, §6, §6.

- [20] (1923–1927) Die neure Entwicklung der analytischen Zahlentheorie. In Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften mit Einschluss ihrer Anwendungen, Band II, 3. Teil, 2. Hälfte, H. Burkhardt, W. Wirtinger, R. Fricke, and E. Hilb (Eds.), pp. 722–849. Cited by: §3.

- [21] (2009) Low-dimensional geometry: from Euclidean surfaces to hyperbolic knots. Student Mathematical Library, Vol. 49, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI. Cited by: §7.

- [22] (2011) Natural boundaries and spectral theory. Adv. Math. 226 (6), pp. 4902–4920. Cited by: §10.

- [23] (1991) History of continued fractions and Padé approximants. Springer. Cited by: §3.

- [24] (1995) Sums of fractional parts of integer multiples of an irrational. J. Number Theory 50 (2), pp. 181–192. External Links: ISSN 0022-314X, Document, Link, MathReview (Oto Strauch) Cited by: §8, §8.

- [25] (2012) Distribution modulo one and Diophantine approximation. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, Cambridge University Press. Cited by: §12.

- [26] (1993) Complex dynamics. Universitext, Springer. Cited by: §11.

- [27] (1957) An introduction to Diophantine approximation. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics and Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press. Cited by: §4.

- [28] (1897) Question 1151. L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens 4, pp. 220–221. Cited by: §3.

- [29] (1973) Exponential sums in the development of number theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Number Theory (Moscow, September 14–18, 1971), I. M. Vinogradov, A. A. Karacuba, K. I. Oskolkov, and A. N. Paršin (Eds.), Trudy Mat. Inst. Steklov., Vol. 132, pp. 7–26. Cited by: §7.

- [30] (1982) Ergodic theory. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, Vol. 245, Springer. Note: Translated by A. B. Sossinskii Cited by: §4.

- [31] (2014) The origins of Euler’s early work on continued fractions. Historia Math. 41 (2), pp. 139–156. Cited by: §4.

- [32] (1979) Georg Cantor: his mathematics and philosophy of the infinite. Princeton University Press. Cited by: §3.

- [33] (1937) On some infinite series involving arithmetical functions. Q. J. Math. 8, pp. 8–13. Note: Collected Works, vol. IV, pp. 1781–1786 Cited by: §12.

- [34] (1899) Question 1490. L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens 6, pp. 213–214. Cited by: §3, §9.

- [35] (1919) History of the theory of numbers, volume I: divisibility and primality. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington. Cited by: §3, §7.

- [36] (1923) History of the theory of numbers, volume III: quadratic and higher forms. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington. Note: With a chapter on the class number by G. H. Cresse Cited by: §3, §3.

- [37] (1849) Über die Bestimmung der mittleren Werthe in der Zahlentheorie. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, pp. 69–83. Note: Werke, Band II, pp. 49–66 Cited by: §3.

- [38] (1999) Lectures on number theory. History of Mathematics, Vol. 16, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI. Note: Supplements by R. Dedekind, translated from the German by John Stillwell Cited by: §3.

- [39] (2004) Hausdorff dimension and Diophantine approximation. In Fractal Geometry and Applications: A Jubilee of Benoît Mandelbrot, Part 1, M. L. Lapidus and M. van Frankenhuijsen (Eds.), Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics, Vol. 72, pp. 305–347. Cited by: §12.

- [40] (1991) Irregular distribution of quadrature of singular integrands, and curious basic hypergeometric series. Indag. Math. (N.S.) 2 (4), pp. 469–481. External Links: ISSN 0019-3577, Document, Link, MathReview (Mizan Rahman) Cited by: §11.

- [41] (1997) Sequences, discrepancies and applications. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Vol. 1651, Springer. Cited by: §8.

- [42] (2004) Lattice points in cones and Dirichlet series. Int. Math. Res. Not. (53), pp. 2823–2836. External Links: ISSN 1073-7928, Document, Link, MathReview (Don Redmond) Cited by: §9.

- [43] (2011) Revisiting the sources of Borel’s interest in probability: continued fractions, social involvement, Volterra’s prolusione. Centaurus 53 (4), pp. 306–332. Cited by: §12.

- [44] (2010) Ergodic theory: with a view towards number theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Vol. 259, Springer. Cited by: §11, §11, §12, §4, §4, §6, §6.

- [45] (1948) Some remarks on Diophantine approximations. J. Indian Math. Soc. (N.S.) 12, pp. 67–74. Cited by: §6.

- [46] (1770) De summis serierum numeros Bernoullianos involventium. Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae 14, pp. 129–167. Note: E393, Opera omnia I.15, pp. 91–130 Cited by: §11.

- [47] (2003) Fractal geometry: mathematical foundations and applications. second edition, John Wiley & Sons. Cited by: §12.

- [48] (1998) Number theory IV: transcendental numbers. Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Vol. 44, Springer. Note: Translated from the Russian by Neal Koblitz Cited by: §5, §9.

- [49] (2007) Labyrinth of thought: a history of set theory and its role in modern mathematics. Second Revised edition, Science Networks. Historical Studies, Vol. 23, Birkhäuser. Cited by: §3.

- [50] (1992) Newton, Cotes, and : a footnote to Newton’s theory of the resistance of fluids. In The Investigation of Difficult Things. Essays on Newton and the History of the Exact Sciences in Honour of D. T. Whiteside, P. M. Harman and A. E. Shapiro (Eds.), pp. 355–368. Cited by: §4.

- [51] (1999) The mathematics of Plato’s Academy: a new reconstruction. second edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Cited by: §3.

- [52] (1898) Question 1260. L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens 5, pp. 77. Cited by: §3.

- [53] (1899) Question 1547. L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens 6, pp. 149–150. Cited by: §3.

- [54] (2007) Resonances and small divisors. In Kolmogorov’s Heritage in Mathematics, É. Charpentier, A. Lesne, and N. K. Nikolski (Eds.), pp. 187–213. Cited by: §11.

- [55] (1994) Concrete mathematics: a foundation for computer science. second edition, Addison-Wesley. Cited by: §7.

- [56] (1969) On the sum and numerical integration. Pacific J. Math. 31 (2), pp. 383–394. Cited by: §6.

- [57] (1922) Some problems of Diophantine approximation: the lattice-points of a right-angled triangle. Proc. London Math. Soc., Ser. 2 20, pp. 15–36. Note: Collected Papers, vol. I, pp. 136–158 Cited by: §3, §8.

- [58] (1946) Notes on the theory of series (XXIV): a curious power-series. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 42 (2), pp. 85–90. Note: Collected Papers, vol. I, pp. 253–259 Cited by: §11, §11, §11, §11, §11, Acknowledgments.

- [59] (1979) An introduction to the theory of numbers. Fifth edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Cited by: §3, §3, §5, §5, §7.

- [60] (1940) Ramanujan: twelve lectures on subjects suggested by his life and work. Cambridge University Press. Cited by: §12.

- [61] (1966) Collected papers of G. H. Hardy. Vol. I, Oxford University Press. Cited by: §12, §3, §3.

- [62] (2007) Problems and solutions in real analysis. World Scientific. Cited by: §10.

- [63] (2001) Lebesgue’s theory of integration: its origins and development. second edition, AMS Chelsea Publishing, Providence, RI. Cited by: §3.

- [64] (1992) Continued fraction Cantor sets, Hausdorff dimension, and functional analysis. J. Number Theory 40, pp. 336–358. Cited by: §12.

- [65] (1884) Sur quelques conséquences arithmétiques des formules de la théorie des fonctions elliptiques. Acta Math. 5 (1), pp. 297–330. Note: Œuvres, tome IV, pp. 138–168 Cited by: §3.

- [66] (1986) Über die Entwicklung der Theorie der Gleichverteilung in den Jahren 1909 bis 1916. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 36 (3), pp. 197–249. Cited by: §3.

- [67] (1991) Geometric and analytic number theory. Universitext, Springer. Note: Translated from the German by Charles Thomas Cited by: §9.

- [68] (1959) Die Abschätzung von Exponentialsummen und ihre Anwendung in der Zahlentheorie. In Enzyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften mit Einschluss ihrer Anwendungen, Band II, 2. Teil, Heft 13, Teil I, M. Deuring, H. Hasse, and E. Sperner (Eds.), pp. 1–123. Cited by: §8.

- [69] (2002) Metrical theory of continued fractions. Mathematics and Its Applications, Vol. 547, Kluwer Academic Publishers. Cited by: §4, §6.

- [70] (2004) On Davenport expansions. In Fractal Geometry and Applications: A Jubilee of Benoît Mandelbrot, Part 1, M. L. Lapidus and M. van Frankenhuijsen (Eds.), Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics, Vol. 72, pp. 273–303. Cited by: §12.

- [71] (1981) The problem of the invariance of dimension in the growth of modern topology, part II. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 25 (2–3), pp. 85–266. Cited by: §4.

- [72] (1987) Lectures on a method in the theory of exponential sums. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Lectures on Mathematics, Vol. 80, Springer. Cited by: §12.

- [73] (1957) On a series of cosecants. Nederl. Akad. Wetensch. Proc. Ser. A 60, pp. 265–267. Cited by: §12.

- [74] (1959) Statistical independence in probability, analysis and number theory. Carus Mathematical Monographs, Mathematical Association of America. Cited by: §12.

- [75] (1995) Classical descriptive set theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Vol. 156, Springer. Cited by: §4.

- [76] (2016) Infinite ergodic theory of numbers. De Gruyter. Cited by: §12.

- [77] (1959) On a series of cosecants. II. Nederl. Akad. Wetensch. Proc. Ser. A 62, pp. 110–119. Cited by: §12.

- [78] (1997) Continued fractions. Third edition, Dover Publications. Note: Translated from the Russian External Links: ISBN 0-486-69630-8 Cited by: §12, §12, §6, §6, §6.

- [79] (2011) Self-similarity and growth in Birkhoff sums for the golden rotation. Nonlinearity 24, pp. 3115–3127. Cited by: §11.

- [80] (1984) -Adic numbers, -adic analysis, and zeta-functions. second edition, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Vol. 58, Springer. Cited by: §2.

- [81] (1936) Diophantische Approximationen. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Vol. 4, Julius Springer, Berlin. Cited by: §3.

- [82] (1940) Prof. Dr. Jérôme Franel, 1859–1939. Verhandlungen der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 120, pp. 439–444. Cited by: §3.

- [83] (1985) Ergodic theorems. De Gruyter Studies in Mathematics, Vol. 6, De Gruyter. Note: With a Supplement by Antoine Brunei Cited by: §6.

- [84] (1966/1967) Estimates of . Acta Arith 12, pp. 229–261. External Links: ISSN 0065-1036, MathReview (S. Knapowski) Cited by: §6.

- [85] (1974) Uniform distribution of sequences. John Wiley & Sons. Cited by: §6, §6, §6, §6, §8, §8, §8, §8, §8, §8, §8, §8, §8.

- [86] (1992) Number theory and dynamical systems. In The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Number Theory, S. A. Burr (Ed.), Proceedings of Symposia in Applied Mathematics, Vol. 46, pp. 35–72. Cited by: §11.

- [87] (1999) Number theory zeta functions and dynamical zeta functions. In Spectral Problems in Geometry and Arithmetic, T. Branson (Ed.), Contemporary Mathematics, Vol. 237, pp. 45–86. Cited by: §6.

- [88] (2014) Secant zeta functions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 409 (1), pp. 197–204. Cited by: §9.

- [89] (1901) Question 1151. L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens 8, pp. 140–143. Note: Collected Works, vol. 1, pp. 184–187 Cited by: §3.

- [90] (1909) Handbuch der Lehre von der Verteilung der Primzahlen, erster Band. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig and Berlin. Cited by: §6.

- [91] (1924) Bemerkungen zu der vorstehenden Abhandlung von Herrn Franel. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse, pp. 202–206. Note: Collected Works, vol. 8, pp. 166–170 Cited by: §7.

- [92] (1966) Introduction to diophantine approximations. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. External Links: MathReview (W. J. LeVeque) Cited by: §4, §4, §6, §6, §6, §8, §8.

- [93] (1994) Eisenstein’s misunderstood geometric proof of the quadratic reciprocity theorem. College Math. J. 25 (1), pp. 29–34. Cited by: §3.

- [94] (2008) Bernhard Riemann 1826–1866: turning points in the conception of mathematics. Birkhäuser. Note: Translated from the German by Abe Shenitzer Cited by: §3.

- [95] (2000) Reciprocity laws: from Euler to Eisenstein. Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer. Cited by: §3.

- [96] (1904) Question 1547. L’Intermédiaire des mathématiciens 11, pp. 144–145. Cited by: §3.

- [97] (1904) Sur un série analogue aux fonctions modulaires. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 138, pp. 952–954. Cited by: §9.

- [98] (1999) The size of for on the unit circle. J. Number Theory 76 (2), pp. 217–247. External Links: ISSN 0022-314X, Document, Link, MathReview (Michael Drmota) Cited by: §11.

- [99] (2003) Quasianalytic monogenic solutions of a cohomological equation. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI. Cited by: §11.

- [100] (1972) Algebraic numbers and harmonic analysis. North-Holland Mathematical Library, Vol. 2, North-Holland Publishing Company. Cited by: §12.

- [101] (2006) Dynamics in one complex variable. third edition, Annals of Mathematics Studies, Princeton University Press. Cited by: §4, §5.

- [102] (2006) Multiplicative number theory I: classical theory. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, Vol. 97, Cambridge University Press. Cited by: §2, §2, §2, §7.

- [103] (1994) Ten lectures on the interface between analytic number theory and harmonic analysis. CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI. Cited by: §7.

- [104] (1950) Some aspects of Hardy’s mathematical work: Diophantine approximation. J. London Math. Soc. 25, pp. 109–114. Cited by: §12.

- [105] (1964) Na nekotorykh ryadakh po trigonometricheskim funktsiyam. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. 28 (1), pp. 53–62. External Links: ISSN 0373-2436, MathReview (J. E. Cigler) Cited by: §12.

- [106] (2012) Rational number theory in the 20th century: from PNT to FLT. Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer. Cited by: §3, §7.

- [107] (1996) Additive number theory: the classical bases. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Vol. 164, Springer. Cited by: §7, §7, §7.

- [108] (1978) Riemann’s example of a continuous, ‘nondifferentiable’ function. Math. Intelligencer 1 (1), pp. 40–44. Cited by: §3.

- [109] (1991) Hardy-Littlewood problems on the uniform distribution of arithmetic progressions. Math. USSR-Izv. 36 (1), pp. 169–182. External Links: ISSN 0373-2436, MathReview (Z. Kryžius) Cited by: §11.

- [110] (1922) Bemerkungen zur Theorie der Diophantischen Approximationen. Abhandlungen aus dem mathematischen Seminar der Hamburgischen Universität 1, pp. 77–98. Note: Collected Mathematical Papers, vol. 3, pp. 57–78 Cited by: §3.